My bacon has a first name. Actually, two.

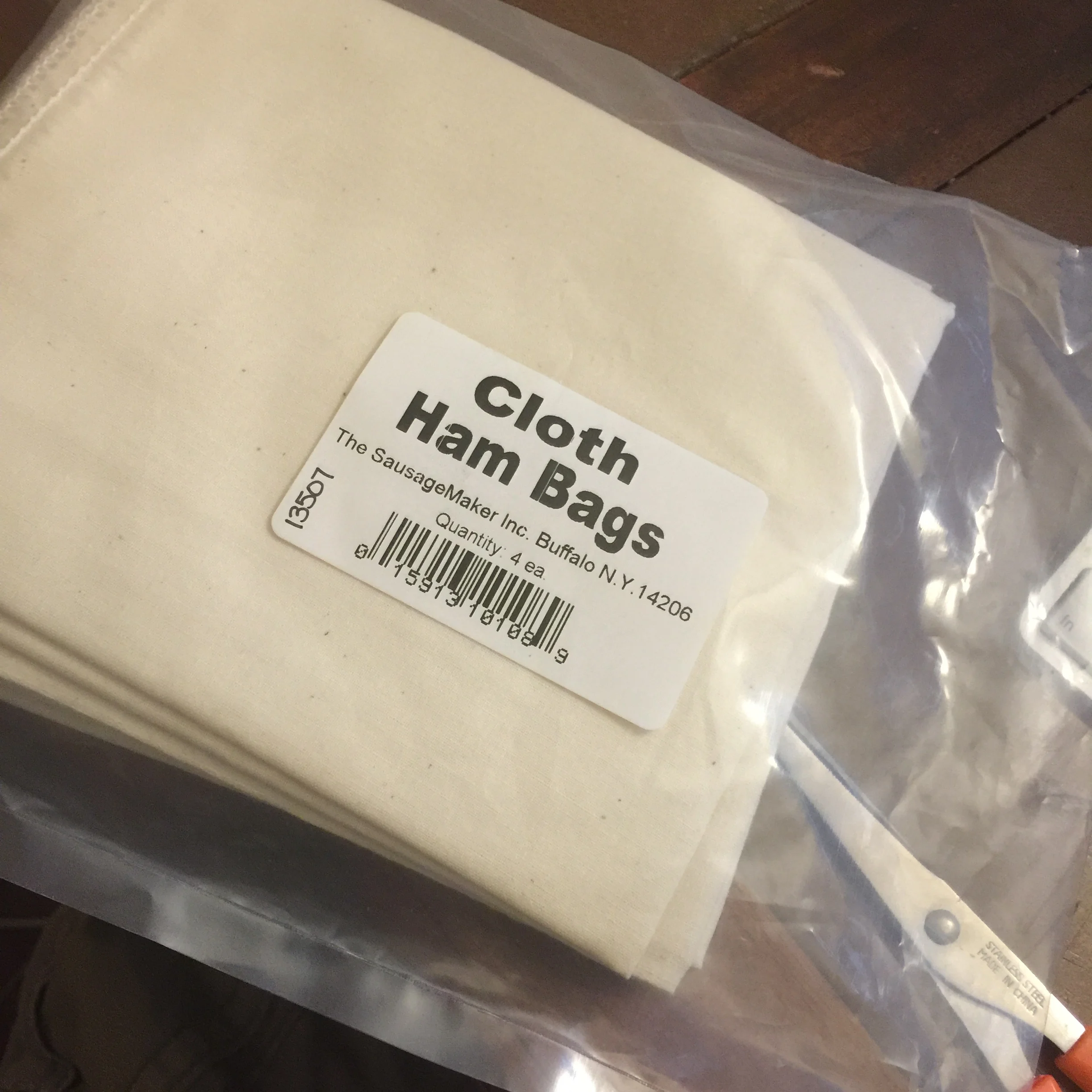

/I love this time of year. This is the time of year that things like this start showing up in my mailbox.

We got our pigs a little early this year - they were born in early February, and we picked them up right around the first of March. So these little bacon seeds got to experience snow (it being Maine, which is about 3 miles from the North Pole, and snow being a thing that we can experience up through and sometimes into May.)

Oh how quickly they grow up. This year's pair of pigs were a Tamworth-Yorkshire cross. They were a nice, long 'bacon' pig.

I'm not making that up. There's math behind that truth. Long pigs == long belly. And pork belly is where they keep the bacon. This differs from our previous pigs, both sets of which were Gloucester Old Spots, which had a richer, thicker layer of fat, and were 'ham' pigs.

I mean, these also have hams. Just a little smaller by comparison.

In the end, I didn't really like these pigs. Not like the Gloucesters, which I'd gladly get again.

Beth (named by my 14 year old daughter who named her after the girl that dies in 'Little Women'), and Apples were constant rooters, and a fairly destructive. They tore the sill out of the back of the barn, pushed random boards in the walls until they cracked and broke, and pushed I'm not sure how many holes through their fencing. The never actually tried to escape, which makes them simultaneously a) idiots and b) far less work than our last set. But I kept having to patch the fence and generally grumble a lot more than I did in the past.

When I looked over at them a couple of weeks ago and sized up their hams by eye, I figured it was time enough for them to head to slaughter. It was not a tearful parting.

We had fed these on the same mix of peanuts and pig feed as we raised the previous sets. the peanuts are my American stand in for the acorns that the deliciously famous black Iberian pigs find in the oak scrub of northern Spain.

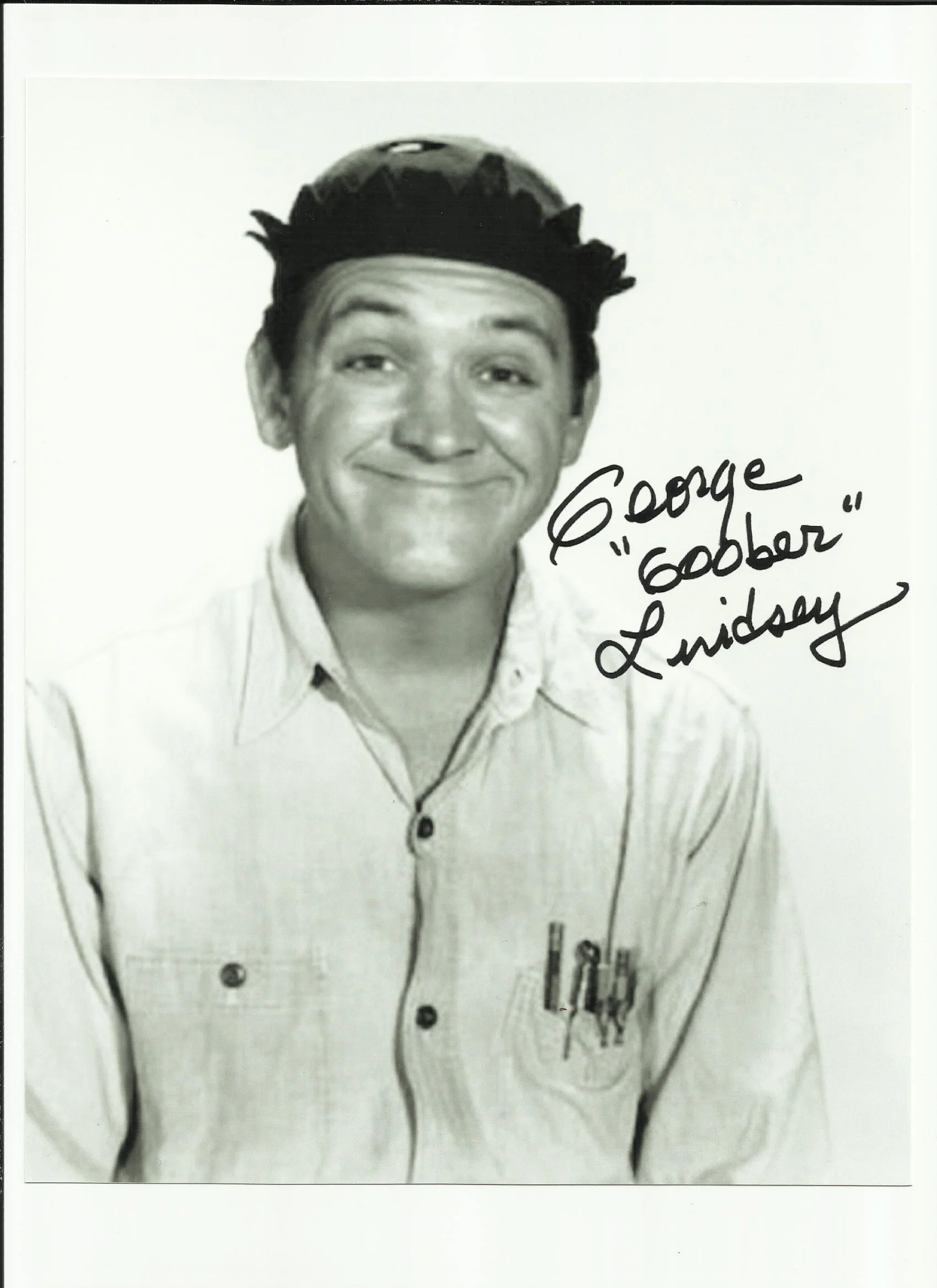

Another nice surprise about moving to Maine is that the peanuts in the shell are about a third cheaper than they are in the feed store in Massachusetts. I have no idea why that might be - I am left to assume that the Massachusetts state legislature has placed a stiff import tax on underground legumes and anything that goes by the common name of 'Goober'. Which is probably also why the Andy Griffith show never took off with the Boston crowd.

I called my buddy down the road and asked if he'd help me schelp the pigs to the slaughterhouse again this year. Actually, I was really hoping his wife would help. Joanna grew up on a local farm, and with their kids, she's a fixture at the local fairs, prepping and herding the animals for show. When she came, she pointed at Joe and myself and showed us where we could stand so we'd be more or less out of the way while she picked up each pig and threw them into the trailer with a gently frightening, backhanded toss of one wrist.

Or something like that. I've watched her in action twice now, and I still have no idea how that tiny little blonde woman gets them in there but they were loaded and ready to go in about 15 minutes.

I tried a new slaughterhouse this year - a local one just down the road in Windham, Maine. It was a self-service drop off on a Sunday morning: back the trailer up, pick a pen and settle them in. There's no staff around, you just fill out a form and fill out the instructions with a contact phone number. (Joanna showed me where the forms were. Of course).

The pigs were pretty much a perfect weight when we took them in - 241 and 242 pounds respectively. That's at the top end of where you want them, more or less. Though there were a pair of pigs in the pen next to these that must have been approaching 500 lbs. Not that I'm fat shaming. But anything north of 250, and you're pretty much just raising lard.

I was a little nervous about trying a new slaughter house. Most slaughterhouses will also butcher and package the meat - many (including this one) even offer smoking and curing. But the ones up here have a fairly limited selection of cutting skills.

I spoke to the owner when I called to schedule the slaughter and asked if he'd be able to cut prosciutto, and back bacon, and a few other traditional cuts. "Sure. We've done that a couple of times."

I mean, cutting a prosciutto isn't hard. It's actually easier than cutting, boning and trimming out your typical ham. Cut the leg off the body. That's pretty much it. So I figured I'd give it a try.

So I crossed out everything on the standard form (which pretty much consisted of "how thick do you like your pork chops" (no pork chops) and "would you like us to go ahead use Pappy's special cure on your sausage? (No). ) and wrote a paragraph or two of instructions on the back of the page. Which pretty much read like this:

"Hi. I make prosciuttos. DON'T CUT THE FEET OFF. Please cut the hip fairly high, because I will cure the whole leg. DON'T CUT THE FEET OFF. These will be things of beauty, which I will tenderly rub with salt and say nice things to. DON'T CUT THE FEET OFF. They will be hung in my basement and brought out to serve the most beloved of guests, to a kind of wordless, heavenly aria sung by small children garbed in white hired specially for the occasion. DON'T CUT THE FEET OFF. It will take two years, but that's ok. Because I believe in long term relationships. And also cuddles. DID I MENTION THE FEET? NOT OFF."

Guess what? They cut the feet off.

The rest of the meat was cut pretty well. The butcher was good, it's just that not a lot of people want to cure a whole ham. So they just instinctively reached for the feet chopper. And once they're off, there's no putting them back on.

I ended up with a lot of trim, and the butts were cut down a bit smaller than I would have liked (can't get coppa out of this). But the loins were handled perfectly - kept whole, with a bit of belly attached. Perfect for making English bacon. And the freezers are now crammed full in a sort of three dimensional meat jigsaw puzzle. And the meat overall looked lovely. Farm to table takes on a whole new meaning of delicious when the farm in question is your backyard.

A couple of days later, we had some guests over (for the Color Wars party), and I smoked up a shoulder to serve. Which was mouth watering.

"Hey kids! This pig was alive in our backyard a couple of days ago! Would you like a bit more Beth on your sandwich?"

I have learned a couple of things about early pigs. Mostly: early pigs get slaughtered early.

It turns out - there's a reason why pig slaughtering season is in the fall, when the air is cool. Because heat does bad things to pork, even with 40 pounds of salt spread over it.

The (footless) prosciuttos (above) went into my prosciutto salting boxes on a nice bed of kosher salt, and were liberally rubbed, coated and massaged with several dozen pounds of salt. And also: salt.

There are three things you can lose a prosciutto to, more or less. Bacteria, pests/insects, or fungus. Any or all is bad. I'd been working on my turning what used to be a dairy room in the basement into a curing room. The stone walls are still whitewashed, and I'd gotten the humidity pretty stable, hovering between 40-55%. I have been charting it out via a SmartThings monitor that would text my phone when it went outside of the range. Basically, I am turning my house into SkyNet in the quest for a good piece of prosciutto.

I visited my prosciutto often. I covered the boxes with a couple of layers of cheesecloth to ensure nothing would disturb them. I watched the humidity closely, and went to sleep each night feeling better that my basement was full of lovely pork.

Until my basement began to smell.

The cut feet not only made the potential-prosciutto harder to hang (you can cut a slit right behind the ankle tendon that makes a perfect place to thread a rope), and less lovely to present, but it doesn't actually affect the meat. So I went ahead with the cure. There's a formula about how long to salt the ham before hanging, based on weight and thickness, and how many letters from Leondardo da Vinci's name also appear in your name. But it is measured in weeks. The next step is to bag it (to keep the flies off for a while longer) and hang it to air dry until your 4th grader is ready for 6th grade.

Unfortunately, because our pigs were ready for slaughter so early in the year, I was starting the cure during the hottest week of the summer. It was in the 90's pretty much every day. And while the basement of this old farmhouse tends to stay a little cooler than that, it is not hermetically sealed. Or air conditioned. And that extra cut at the top of the leg with the bone sticking out provided for a difficult to seal entrance for more bacteria. It was kind of like a marquis board flashing: "HEY E.COLI! I GOT THE THING THAT YOU LIKE RIGHT HERE!" There's a reason that Pa Ingalls waited until the nights were cold and the leaves were falling to slaughter his pigs.

After ten days or so, my meat started to spontaneously juice.

Juiced meat is not a good sign. There's a book I read and keep handy on the shelf called "Ham: An obsession with the hindquarter". (I raise pigs in my backyard so that I can put their hindlegs in a box in my basement. Of course I own this book). In it, the author answers the question, "how do I know if my ham has gone bad" by explaining:

Trust me. You'll know.

He was right.

Sigh... ah well. The bacon's still good, and I have a two prosciuttos from past pigs that will soon be ready. Therefore, I hereby declare this the year of salami. I've got plenty of trim, and nothing but time to get it right.

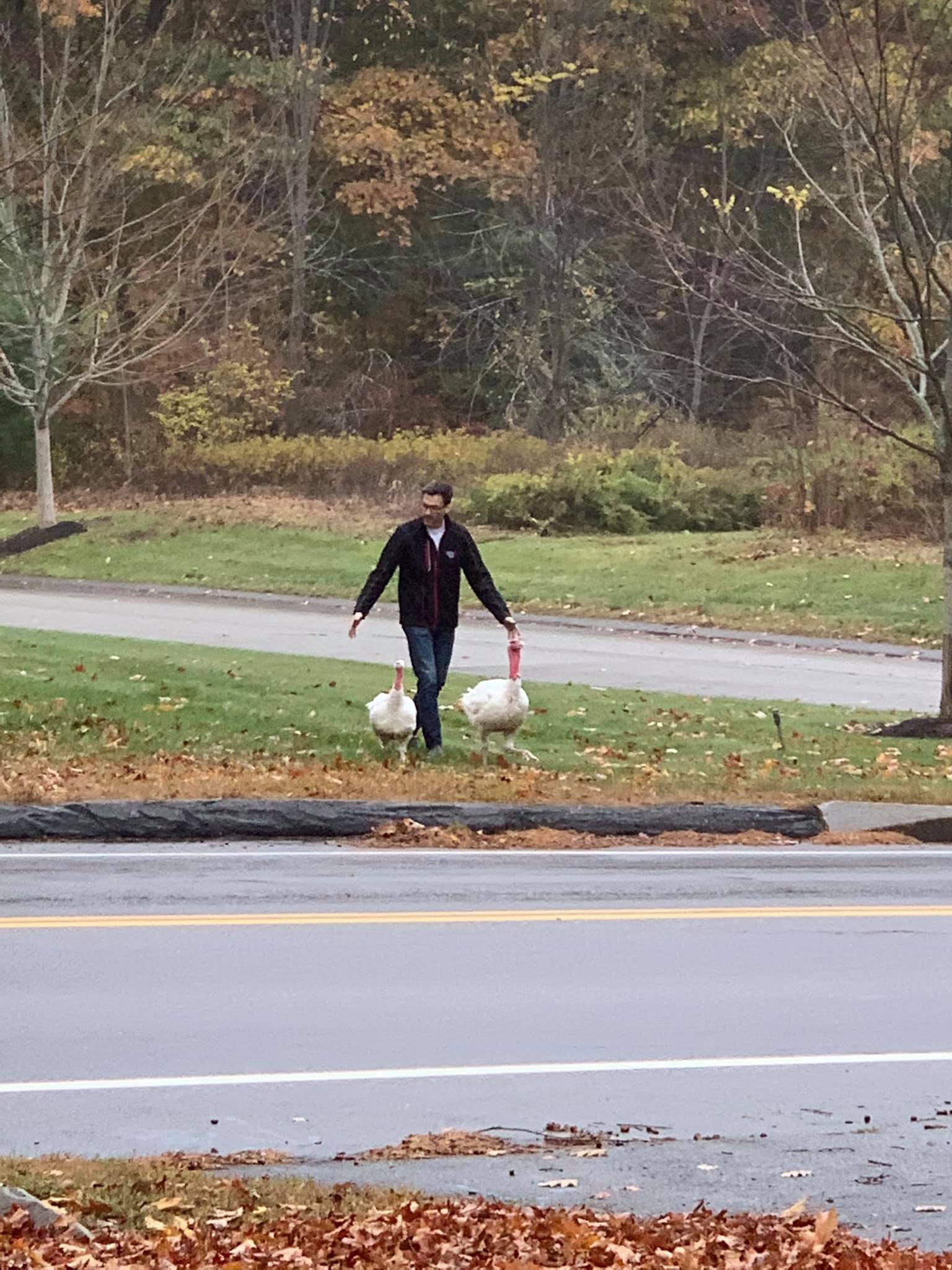

Meanwhile, here's a picture of Apples, taking a leisurely soak.