On death and deviled eggs

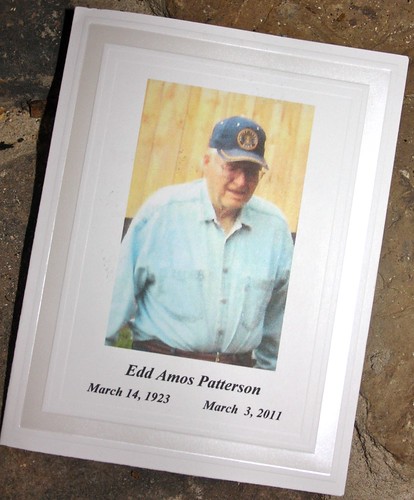

/This past week, my last surviving grandparent passed away. He was a miner, a farmer, a die-hard democrat. He spoke fewer than 100 words to me in the last 15 years. Maybe twice that in the 15 years before that. He was, it turns out, one of the biggest influences in my life.

I have said before that I do not mind so much that I am getting older: The inexplicable pains and creaks encourage me to take a little more time to enjoy my mornings. The grey hairs mating and proliferating on my head are little banners of welcome to the additional hairs sprouting from all-together new places on my body. The decreasing patience with foolish people is offset with a declining interest to point that foolishness out. I try out new forms of crotchetiness like a kid choosing which of Santa's sparkling gifts to open next, and savor each with quiet contentment. I find myself enjoying immensely the simultaneous mellowing and ripening of my adulthood. However, watching the people around me get older - in a word - sucks.

My mother's parents were Appalachia of the old school. They were the salt of the earth you've read about. The Depression kids that sanctified FDR (and by extension, every Democrat since) for bringing jobs, electricity and hope to the hills of the rural South. They knew everybody in their town, didn't have a lot of interest in what was going on beyond it other than to complain about the intrusiveness of it all, but were ready to lend a helping hand if you needed it, without question or hesitation.

Where my grandmother (who passed away almost twenty years ago) was the prototypical grandmother of a Norman Rockwell painting - loving, big-bosomed, rosy cheeked and with a plate full of powdery, hot biscuits ready at hand - my grandfather ('Papa') was downright gruff. He rarely laughed and doled out his words as if there would be a tally at the end of his life, and St. Peter was counting on having some left over.

Papa went to work at the nearby copper mine when he was 19, doing "pretty much whatever they told him to do". He courted my grandmother when they were still in their teens, and built a house at the foot of a valley outside of Blue Ridge, Georgia on land his father farmed. The wood came from their saw mill, and he continued to work the land to grow corn, beans, potatoes and by turns, pretty much any other vegetable that would grow in that area. They raised four kids, were proud to see them all graduate high school, and content to watch the corn grow in the fields and have the children and then grandchildren (and then great-grand-children) return to visit their valley. It was a little slice of heaven for him. And a ritual summer & Christmas destination for us kids.

I got word of my grandfather's death last Thursday afternoon. That night, we decided that we'd pack the kids and the dog in the back of the car after work the next day, and head down to see my parents, and then over the hills into Georgia to attend the funeral and bid farewell. It is an 18 hour drive to my parents in Tennessee, and then another 4 hours into the Georgia mountains. I had not been back to see my grandfather or much of the extended family in years.

I thought about the first time I introduced my Bride to Papa. The living room in his house was dark and smelled the way only a house continuously lived in for 50 years can. He sat in his overstuffed chair, and in his way, I could see him try to find a connection to this young, pretty Filipina I was introducing him to. I was the first of the family to marry a non-white woman. Even worse: she was from California.

"I served in the Philippines in The War. After we pushed the Japs out. My brother Kimsey had been killed by a Jap bomb, and so I got stationed on shore for a while."

The conversation lapsed quickly from there.

A year or so after my Bride and I were married, we heard that Papa was getting married again to a sweet woman at the small church he attended. They made each other happy, and it was funny for me to think that my Bride and I would no longer be the newlyweds in the family. This was also the first time, I think, that I introduced my Bride to the aunts and uncles. The weekend was a bit of a blur, and I don't remember much of how things went, other than the fairly wretched guitar-playing singer that accompanied the event. The guy was in his early 30's, serenading two contented septagenarians planning to help each other through their sunset years through bad Barbara Mandrell cover songs. Hey, if they were happy, I was happy.

Over the remaining years, we kept in increasingly sporadic contact. Mostly an annual Christmas card. I have always been notoriously bad at keeping in touch with people (one of the main reasons I started this blog), and though I can vouch for the fact that Papa did, in fact, actually own a phone, you could not prove that his phone actually dialed out from his use of it.

As we drove through the night down I-84, therefore, I was more worried about my how my mother was dealing with his passing than I was actually grieving my grandfather. I had been close to my grandmother. I knew and respected my grandfather. But I couldn't point to enough relationship between us that would now be no more. That left me a little emptier to think about. But not really saddened, as such.

I was, however, very conscious that my children have never been to a funeral before, as we neared the funeral home. The Critter is 8, and the Boy is 3, and they both (especially the former) certainly get the concept. The recent death of the Critter's namesake a few months ago made it real for both of them, but hers was a small service that we couldn't attend, and she had been cremated. No body to see. Move along.

This time around, however, we were nearly the first ones to the funeral home this time, and my grandfather had been laid out in a viewing room, coffin draped in a flag to mark his Naval service. The Boy was wide-eyed, and both of the kids had a death grip on my hands.

The Boy craned his neck and stood up on his tip toes to see over the casket rim. "Is your friend dead?"

"Yes, son. That was my grandpa. And yes, he's dead now."

"Did the bad guys shoot him?" Oh geez. Remind me when we get home - less XBox for you, kid.

"No, son. He was simply very old, and tired. And that happens to all of us sooner or later."

The Boy was solemn, and the Critter was somewhat pale, but we all stood together and looked at the shell that had been my grandfather for a while.

My mother's sister, Aunt Potty (Paulette, but I couldn't pronounce that when I was a kid, and choose not to now), had assembled a collection of photographs from over the last years and a local company had worked to put it to a digital slide show and music that was playing in the corner of the room. There were the normal fuzzy black and white shots of his early marriage, a growing number of small children in their arms. Pictures of him hunting, of him holding a trophy buck. Pictures of a scant few vacations to various places within driving distance. Pictures of him as now an aging grandfather, holding a new crop of infants with surprising care.

About half of the photos, though, were of him in his garden. Several acres of the property were always, always tilled and planted. And seeing the pictures of him on the tractor, sewing, weeding, picking over the grape vines and corn stalks - suddenly, it struck me that I did, after all, have a surprisingly strong connection to the man who had just passed away. My father, The Surgeon loved to tend his rose bushes, but never taught me when to harvest potatoes. My step-father, the Carpenter, has embedded in me what it meant to be self-reliant, but did not show me the joy of eating the fruits of my own labor.

Rather, every summer for most of my early years I was deposited for weeks on end at my grandparents' house, and left to fend for myself. My grandmother would shower hugs on me, and take me to the Piggly Wiggly or The Fountain cafe for a treat, but during the long hours of the day, I would be sent off with a grunt and a gesture to weed, pick, straighten, or otherwise make myself busy in the garden. I remember being scared of the giant, heavy buzzing bees stalking through the corn tassels, where I couldn't see over the rows of stalks. I picked up rocks from the freshly tilled soil, and dragged weeds over to the brush pile to be burnt. I sat on the back porch for hours, snapping and stringing bushels of green beans in the languid heat, listening together to the rise and fall of the cricket hum.

I stopped spending my summers there when I was 12 or 13, and we mostly stopped the large family gatherings at their house for Christmas around the same time. But when I looked long at those pictures of my grandfather walking up the hill in the sunshine on a path I knew, I realized in a way I had not before what kind of impact this taciturn, stubborn man had made on me. He was as much a part of who I have become as I've grown older as any of my role models, and I can see him manifesting in my growing garden and desire to put up, save, and share the harvest of my by comparison small efforts with my children and neighbors.

I tried to share a little of this with my children as we watched the pictures, and the room filled up around us with other, near and distant family members I hadn't seen in years (or ever). With other cousins showing up around the same age, the Boy soon enough found the somber mood too much to carry, and they were running around underfoot of their tolerant elders, playing together. I did have to admonish him a couple of times not to try his normal tricks out.

"I don't care if we are in North Georgia, son, and if they are all blonde and blue-eyed. You do not flirt with your cousins."

The graveside service was wet and cold, but touching, with a full honor guard and 21 gun salute that would have done Papa proud of his service. And even more so - the bell he had donated to his small baptist church was rung during the final prayer.

Finally, cold and damp, we had reached the last stage of a Southern Funeral. We trickled off the cemetery grounds and back to our cars, and headed back to the church basement, where a groaning table had been laid out. A pair of sliced hams. Aluminum trays of fried chicken. A half a dozen warm casserole dishes each of home canned green beans and corn. Mashed potatoes and potato salad cozied up to each other, next to as many varieties of macaroni and cheese as there were families in attendance. Pitchers of sweet tea. And platters of the deviled eggs that are required by Southern law to make their appearance at every picnic, holiday, wedding and funeral.

You can tell who brought which platter of eggs by the various dustings of paprika: the Methodist half of the family showed restraint in their dusting, so as not to seem wasteful. The Baptist part of the clan tended to showy, heavy dustings, as if to make up for the lack of drinking through a touch of quasi-exotic spice.

My children took one look at the table, and headed for the plates. The Critter showed determined energy to make up for not being allowed to muss her somber funeral clothes earlier in the day with the risk of spillage, and piled her plate high before wedging herself onto a bench between her mother and a smiling blue-haired second cousin once removed. The Boy scarfed down a drumstick, and was soon ducking back and forth under the tablecloth with yet another cousin in a giggling game of chase that had the great-uncles smiling on their bench.

This was a Southern funeral of the sort I was glad to bring my children to. Equal parts grief, prayer, family and food. There was a bluegrass hymn sung in the chapel that was more enthusiastic than harmony, and I loved every minute of it. Every car the funeral procession passed in either direction stopped to show respect. And the well-used basement of that small baptist church was full of laughing memories of fatherhood, grandfatherhood, and family. It was an Old South moment in way that I can still aspire to.

And it was thanks to the man that my grandfather had been, the community that he had been a vital, quiet part of, and the family that he had helped build.

He was my hero after all.