Thankful

/After dealing with a pig or two and a cow (technically: a steer) this year, going and getting our own turkey for Thanksgiving seemed like the natural thing to do.

Last year, under circumstances I can't really recall, I entered into a bargain with a co-habitant of our little New England village. He would give me one of the turkeys from his flock for Thanksgiving, and I would in return give him a Christmas ham. It was barter in the best spirit of Hugh Fearnley-Wittingstall's Dorset.

This year, John and I struck our bargain early. I had told him about both our beef and our cheese making efforts, and he was up for pretty much anything. I, on the other hand, am eyeing an aging population of chickens in my backyard, thinking that what's left of the original batch are aimed for the pot in the next six months or so. (For these survivors of fox, hawks - one of which invaded their chicken coop - it may seem like a rather sad end. But their egg-laying days start dwindling after their second full year, and other than one or two favorite 'personalities' that I'll keep around to retire gracefully with the younger birds, the lot of them will end life nobly gracing our table in the most delicious way we can arrange). Problem is, I've never killed a chicken before. And I admit, I'm a little nervous about trying to figure out how to do it on my own, even with all the resources of the internet at my fingertips.

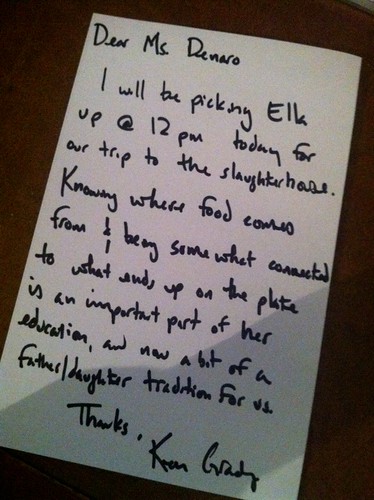

So I asked John if I could join him for the turkey harvest this year as a part of our bargain. I'd help process, if he wouldn't mind imparting a little bit of wisdom and practical experience along the way. And I'd throw in some beef to sweeten the deal.

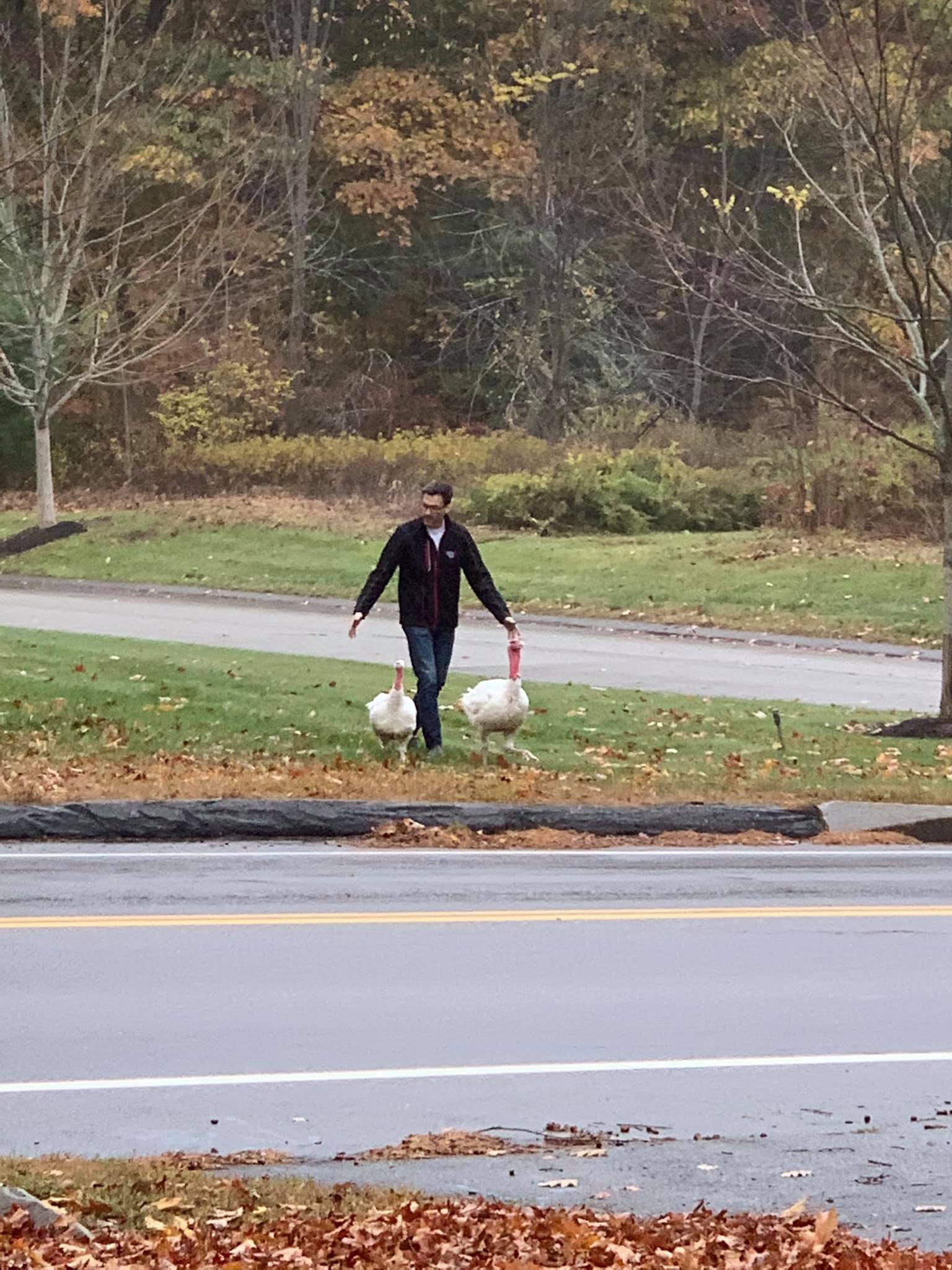

I left work a few minutes early on a crisp Monday-before-Thanksgiving evening to get home and change into something a bit more Turkey-slaughter appropriate. (which was a guess. I had a somewhat un-defined mental image of what I was about to do, but I figured pinstripes and loafers weren't called for.) When I was thus properly attired and I hollered out to the household that I was off, the Critter scrambled out of whatever hole she had been hiding in, and asked to go along.

I was a little surprised, and explained again that unlike the trip to pick up our pig and cow, these turkeys would still be alive when we pulled up. She shrugged and nodded, and hopped in the truck. OK. Well, then. Off we go.

Read More